We have explained a couple of times what microlearning is and why it could be considered a pragmatic innovation for lifelong learning, given that it is coherent with current information and communication patterns.

If we give a step forward towards adult education and training in companies, we’ll discover that it is a subject that worries as much content creators as business owners.

It has become increasingly evident the power of the 2.0 Net and how it influences and modifies the traditional ways of learning. Moreover, our rhythm of life also gives rise to the mismatch of knowledge, what means that it becomes outdated in a really short period of time. It is no longer valid to talk about the “educational stage”, given that we never stop learning.

When we analyze microlearning as a training strategy, we often mention human’s ability to remember, assimilate and retain only 4 or 5 concepts per day.

Magical number: seven plus or minus two

George Miller, a cognitive psychology pioneering, introduced his theory “Magical Number Seven, plus or minus two” in 1956.

Miller detected one limitation in the abilities related to cognitive processes. In one of his experiments he showed a number of colored shapes to an individual and related each color to one arbitrary word (always the same word for each color).

The number of words (word-color connections) was different for each experiment. Naturally, when there were not many, participants showed a better execution than when there were lots of them, since mistakes increased substantially.

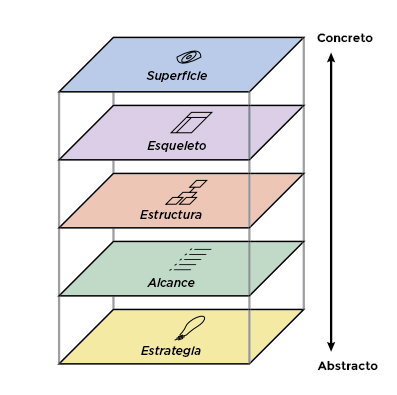

It turns out to be interesting that in all these experiments appeared an odd regularity regarding the number of elements that a participant recognized, categorized or memorized all along an evaluation. In the majority of the works the optimal execution rates were of a maximum between 5 and 9 elements. That is to say, 7 with a deviation of 2. Beyond this, the system was “overloaded” or “overwhelmed”.

Afterwards, in the 21st century, other authors as Nelson Cowan developed this theory and proved that the short-term range of information that we are able to remember is between 3 or 5 elements.

Working memory

The “working memory” is the temporary memory that we use in order to carry out a task or to solve a determined problem. It was a concept introduced in 1974 by Baddeley, which has evolved over the years.

When we talk about working memory, we talk about those processes that are used in mental tasks (to retain ideas to combine them with other to come), in problem solving (to remember the numbers in calculation processes) and in planning (to determine the best route to arrive at some point).

Imagine that somebody asks you to do a mathematical computation. Let’s say, for example, to multiply 56 by 23, without calculator and without writing down. First of all, you will need to keep in your working memory these two numbers. The next step will be to use the multiplication rules that you learnt in the past in order to calculate the product “53 x 3” (using again your working memory to remember the tens you carry). Later on, you will do the same with 56 x 2. You will have to add to your working memory the results of these pair of computations to finally obtain the correct answer.

Without this working memory, we would not be able to carry out this kind of complex mental activities, in which we need to retain certain information while we process a different material.

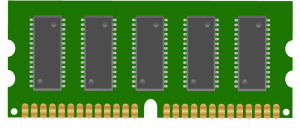

This metaphoric RAM memory isn’t as easy to quantify as in computers, given that there are multiple mechanisms related to the retention of information and variables that intervene and that depend on the abilities of each person. Nonetheless, different research has demonstrated that this operative memory does not last for more than 2 seconds. After this period of time, if we do not perform some repetition (phonological loop), the new information is forgotten.

Conclusions

There are still discrepancies between scientifics who study the processes occurring in our brain and analyze how our memory works.

A lot of them, as we have reported, establish that there is a working memory, a short-term memory and a long-term memory. While others claim that the dissimilarities between one kind and the other are not as evident as to mark a clear separation.

It is difficult to determine if microlearning rises from this theory or if it is focused in a completely pragmatic question (short time – short content). In spite of it, everything seems to point out that when we acquire some knowledge from small pieces of information, in a small quantity, and in a frequent way, we do it better than when information is introduced in big portions.

Post translated by Carolina Serna